Documents reveal Tassal wanted two reports on antibiotic use at salmon farms kept secret

Right to Information documents reveal that Tasmania’s largest salmon company sought to block the public release of monitoring reports submitted to the Environment Protection Agency (EPA) after using more than two tonnes of antibiotics at two of its fish farms.

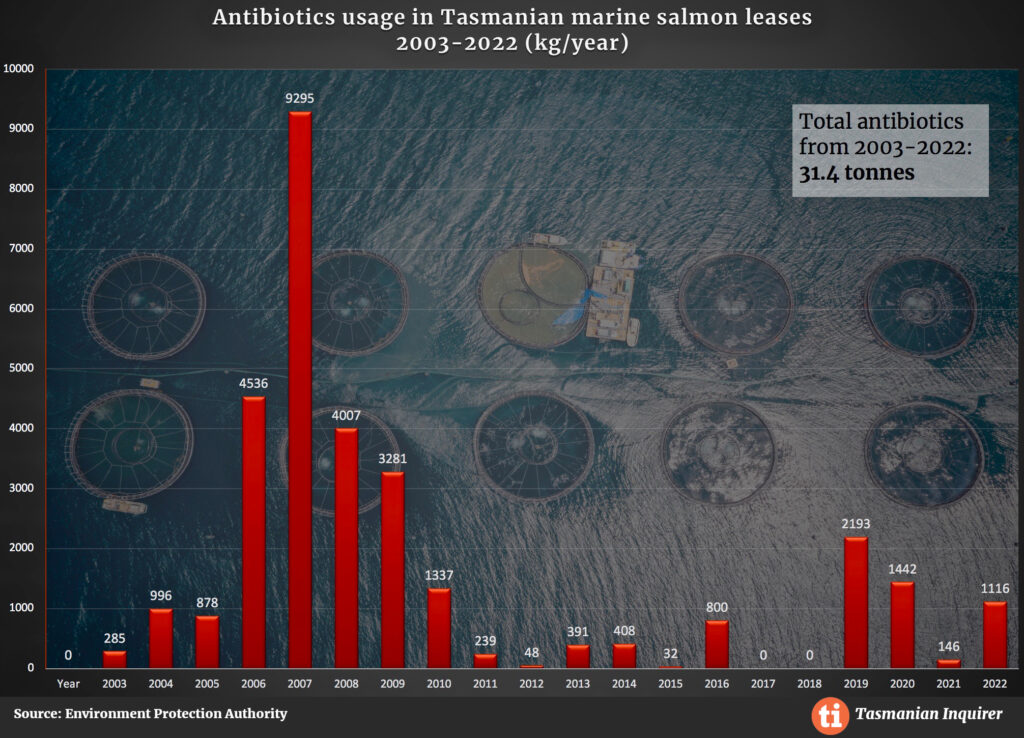

A table in one of the documents disclosed to Tasmanian Inquirer reveals the Tasmanian salmon industry has used more than 31.4 tonnes of antibiotics in marine leases since 2003.

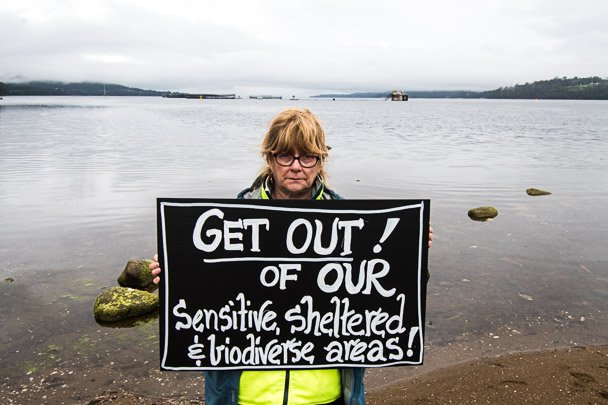

“The use of antibiotics appears to be increasing, which is extremely disappointing, given that vaccines are available. The salmon producers need to lift their game”, said Sheenagh Neill, a spokesperson for Marine Protection Tasmania.

In early January 2022, Tassal and Huon Aquaculture reported outbreaks of vibrio, a bacterium the Tasmanian Salmonid Growers Association says can cause an infection with a “high mortality rate”.

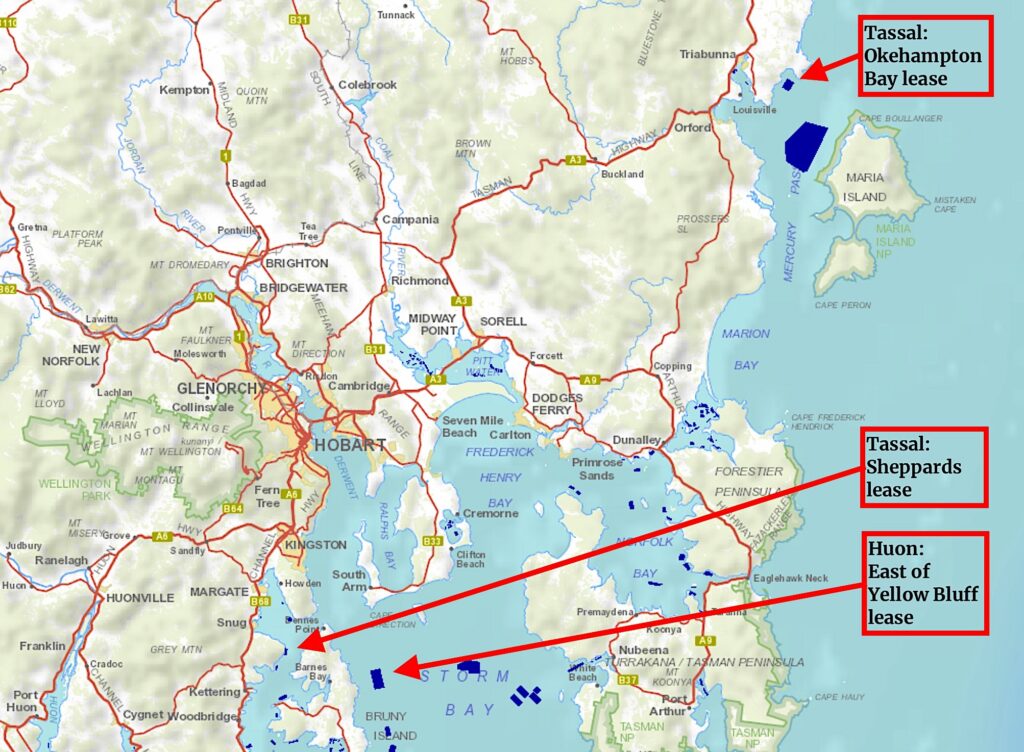

To treat the outbreak, Tassal used 675 kilograms of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, oxytetracycline, at its Sheppards lease near Coningham just south of Hobart. EPA staff reported that there had been “a sticking point” in discussions with Tassal after the company argued the antibiotic residue monitoring report should not be made public.

An internal January 2022 memo to EPA Director and chief executive Wes Ford revealed that there had been a long-running standoff with Tassal over the public release of a September 2020 report on the use of 1.3 tonnes of oxytetracycline at the controversial Okehampton Bay lease near Triabunna.

“Tassal has very good reasons for wanting to keep the public in the dark about their poor animal husbandry practices and their dumping of tonnes of antibiotics into our public waterways: it makes them look bad.”

Sheenagh Neill, Marine Protection Tasmania

According to the EPA, Tassal provided “a number of legal reasons” why the report should not be released in full, including that the information should be considered commercial-in-confidence. The company objected to the publication of details about how much antibiotics was used and the number of salmon cages that were treated.

The EPA informed Tassal of its intention to publish the report on 16 November 2020 unless it could “provide further justification why not”. But the report remained buried until July 2022, when it was published on the EPA website without public notification.

An EPA spokesperson confirmed the agency had been “in dispute” with Tassal “over material contained in the report, and whether or not it should be published”. They said the government amended the Environmental Management and Pollution Control Act in December 2022 to allow the EPA director to release and publish “relevant environmental information”.

Community groups said they were not surprised Tassal didn’t want the full report released.

Neill said: “Tassal has very good reasons for wanting to keep the public in the dark about their poor animal husbandry practices and their dumping of tonnes of antibiotics into our public waterways: it makes them look bad. I’m pleased that the EPA did not pander to Tassal’s wishes.”

‘Double standards’

By the time of the January 2022 outbreaks, the EPA had developed a framework for monitoring and reporting antibiotic residues. It involved taking sediment samples near the fish cages and just outside the lease and flesh samples from wild fish within the lease area and some further away.

There was debate inside the EPA about which sampling locations to use. An EPA officer said it would make “more sense to only sample wild fish/inside adjacent to the lease rather than at sites greater than 500m away”. They argued that it was “extremely unlikely to pick up levels in fish sampled some distance from the lease … other than for optics, it doesn’t make any sense to me to sample at Conningham/Dennes [Pt]/Killora”.

The EPA official cited a 2007 Food Standards Australia New Zealand assessment that concluded recreational anglers would have to consume many serves of antibiotic-contaminated fish to pose a health risk. Despite this, the EPA settled on wild fish sampling at Killora and Nebraska Beach on Bruny Island and Conningham.

The final monitoring report revealed flathead caught off Coningham Beach, two kilometres from the boundary of Tassal’s Sheppards lease, had antibiotics in their flesh above the reportable threshold.

Tassal says on its website that before being slaughtered, salmon treated with antibiotics “must go through a lengthy withdrawal period, as required by the authorities to ensure no residue”. The regulatory withdrawal standard for salmon for the domestic market is 1000 degree days, a cumulative tally based on water temperature. (If the water temperature is steady at 16 degrees, the 1000 degree days threshold is reached on the 63rd day.)

“Why is there a 1000 degree days clearance required for salmon, yet any person fishing for flathead has no idea about possible antibiotic residues in the fish they catch in the ‘wild’?” Neill asked.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that misuse of antibiotics is accelerating the development of antibiotic-resistant organisms. It describes this as “one of the biggest threats to global health”. The WHO has recommended the vaccination of farmed animals as one strategy to reduce the overuse of antibiotics.

The EPA and Huon Aquaculture agreed on the requirements for an antibiotic residue monitoring report after it used 400 kg of trimethoprim to treat salmon at its East of Yellow Bluff lease off the coast of Bruny Island.

But the company acknowledged salmon affected by the vibrio outbreak were unvaccinated. It said it hadn’t previously been an issue at the site. “The aim is that future populations will be vaccinated against vibrio to prevent reoccurrence of this situation,” a company executive wrote in an email to the EPA.

Huon Aquaculture did not reply to questions from Tasmanian Inquirer about whether this change has been implemented. Tassal did not respond when asked if the salmon at the Okehampton and Sheppards leases were vaccinated or would be in the future.

Gerard Castles from the Killora Community Association wrote to Primary Industries and Water Minister Jo Palmer in November 2022 asking why the local community and affected councils were not told about the use of antibiotics at the Sheppards lease. Palmer did not answer the question directly. She said the EPA regulated the industry.

A spokesperson for the EPA did not commit to publicly announcing when approval had been given for using antibiotics at salmon farms, or when new residue reports had been published. They said possible disclosure of this information would be considered as part of a review.

Neill said the public should be “informed in real-time”.

“There are better, world-class options available, and it’s time this government started protecting our waterways and the public that use them,” she said.

(Note: The complete set of Right to Information documents released to Tasmanian Inquirer are here, here, here and here.)

@BobBurtonoz

@BobBurtonoz